By Jeffrey S. Reznick

This Veterans Day is the first to occur during the four-year centenary anniversary of World War I. As media outlets feature stories about medical care and philanthropic support provided to men and women who have sustained permanent injury through military service in recent wars, we have an opportunity to look back to the Great War and remember its veterans and the many generous individuals who advocated for them on the road back to civilian life.

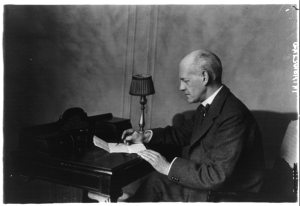

One of those individuals was John Galsworthy (1867–1933), recipient of the 1932 Nobel Prize in literature for his authorship of the The Forsyte Saga, an epic sequence of novels and ‘interludes’ about the upper-middle-class Forsyte family. While Galsworthy is best known for this literary achievement, he should also be remembered for his humanitarian support for and his writings about soldiers disabled in the “war to end all wars.”

For Galsworthy, the weeks running up to the Great War were a time of depression and paralysis. “These war-clouds are monstrous,” he wrote in his diary about the impending conflict. “If Europe is involved in an Austro-Servian [sic] quarrel, one will cease to believe in anything.” He recorded in his diary shortly thereafter: “I wish to Heaven I could work.” Such thoughts about the impending war combined with his marriage (which he viewed as “paralyzing”), with his poor physical health (which involved a “game shoulder” and “short-sightedness”) and with his age of forty-seven (which disqualified him from enlistment) to shape Galsworthy’s perception of himself as disabled.

Galsworthy eventually overcame his sense of disability, and made sense of the war he hated while supporting the nation he loved by embracing his very ability to write as “the most substantial thing” he could do to support “relief funds.” For the duration of the war and through the middle of 1919, therefore, he composed essays of fiction and non-fiction that were not merely descriptive of that damage and efforts to repair it but also personally-reflective as they revealed the thoughts of an observer who was set apart from, but nonetheless wished to participate in, the events of the day.

One of Galsworthy’s most thought-provoking essays was “The Sacred Work,” which he wrote during the spring of 1918 upon request of the Ministry of Pensions for the official proceedings of the second annualInter-Allied Conference and Exhibition on the After-Care of Disabled Men. This piece argued that soldiers who were “broken in war” were a vital portion of the public deserving of health in the postwar era, and that the other segment of the public—namely those civilian noncombatants who remained at home, including Galsworthy himself—had in front of them not only the task of maintaining the public’s health writ large but also “the sacred work” of providing health to the “stricken heroes of the war [who] in every township and village of our countries…will dwell for the next half-century.” Galsworthy continued:

The figure of Youth must go one-footed, one-armed, blind of an eye, lesioned and stunned, on the home where it once danced. Half of a generation can never again step into the sunlight of full health and the priceless freedom of unharmed limbs. So comes the sacred work…Niggardliness and delay in restoring all of life that can be given back is sin against the human spirit, a smear on the face of honour…The ‘scared work’ begins…in special hospitals, orthopaedic, paraplegic, neurasthenic, [where] we shall give back functional ability, solidity or nerve or lung. The flesh torn away, the lost sight, the broken ear-drum, the destroyed nerve,…it is true, we cannot give back; but we shall so re-create and fortify the rest of him that he shall leave hospital ready for a new career. Then we shall teach him how to tread the road of it, so that he fits again into the national life, becomes once more a workman with pride in his work, a stake in the country, and the consciousness that, handicapped though he be, he runs the race level with his fellows, and is by that, so much the better man than they.

The reprinting of this essay in several American publications during the final months of the war reflected what was by then Galsworthy’s international reputation as an advocate for disabled soldiers. Major figures of the day who wrote about rehabilitation programs for wounded soldiers—including Garrard Harris, Cecil W. Hutt, and Douglas McMurtrie—acknowledged Galsworthy’s contributions.

When the Great War ended in November 1918, Galsworthy did not publicly address the subject of disabled soldiers again until 1921, when The Disabled Society published his nine-paragraph foreword to its Handbook for the Limbless. Suggesting the very therapeutic value of his words and theHandbook itself—both for himself and for the nation—Galsworthy wrote that “…It will do a lot of us, who still have all our limbs, good to read this Handbook, and be reminded of what so many thousands are now up against, and of how sturdily they are withstanding discouragement.”

The fact that this short piece was apparently Galsworthy’s final public statement relating to disabled soldiers should not be surprising. Like so many individuals of the “generation of 1914” who survived the Great War, Galsworthy had wanted to forget the trauma of the conflict and the rhetoric of the contemporary culture of care-giving surrounding disabled soldiers, including the promises of artificial limbs, curative workshops, and propaganda that envisioned a positive future for all disabled veterans. Put simply, Galsworthy was through with the war. As correctly prophetic as his wartime compositions were, the empty rhetoric of heroism and false promises of the day prevailed.

So disillusioned was Galsworthy with the war—and so disenchanted was he with his wartime advocacy, which he judged as merely a drop in the flood of propaganda which overtook the nation—that from 1921 until his death in 1933 he never again took up the subject of disabled soldiers in any original way. The war, Galsworthy observed privately in a letter to a friend shortly before his death, “killed a terrible lot of—I don’t know what to call it—self-importance, faith, idealism, in me…”

The experiences and words of John Galsworthy offer a lesson in how quickly wars and veterans can be forgotten. On this first Veterans Day during the centenary anniversary of the Great War, this chapter in the history of that conflict should inspire us not only to remember disabled veterans of subsequent and current wars but also to invest for the long term in “the sacred work” of renewing their health and enabling their full participation in society.

Learn more about John Galsworthy and his work on behalf of soldiers disabled in the Great War, from the BBC World War One at Home, a growing collection of stories that show how WW1 affected the people and places of the UK and Ireland.

Jeffrey S. Reznick, PhD, is Chief of the History of Medicine Division at the National Library of Medicine.

Jeffrey S. Reznick, PhD, is Chief of the History of Medicine Division at the National Library of Medicine.John Galsworthy and disabled soldiers of the Great War, available in paperback, December 2014

http://www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/cgi-bin/indexer?product=9780719096754

No comments:

Post a Comment